Introduction

Male students will require a chaperone to examine female patients.

- Inspection

- Palpation

- Percussion – no need to percuss in the cardio exam!!

- Auscultation

Inspection

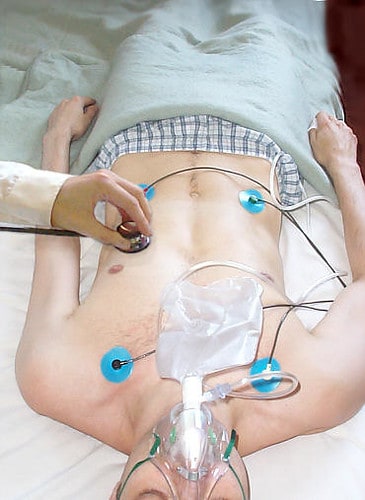

Have a general look around – what sort of equipment is present around the bed?

- An ECG monitor can suggest chest pain and arrhythmia.

- Is the patient distressed and/or in any pain?

- Does the patient have a cannula? This can suggest they are receiving drugs for chest pain or heart failure, and rarely, infective endocarditis.

- Is there a malar flush? This can be suggestive of mitral stenosis as can sweating.

- Tachypnoea can suggest heart failure.

- Cyanosis can suggest heart failure.

- Forceful neck pulsations (carotid) may suggest aortic regurg.

- Ankle oedema can suggest heart failure

Inspect the hands

- Splinter haemorrhages – these are little haemorrhages in the nailbed under the nail. They occur in patients with infective endocarditis. IE will mainly affect the heart valves, but can also cause inflammation of small blood vessels, which may then lead to rupture of the blood vessels, and thus splinter haemorrhages. HOWEVER – they only occur in 10% of IE patients, and are relatively common as a result of normal wear and tear – particularly in manual labour workers. If you want to be especially vigilant you could check the toe nails as well as the fingers. In IE, both are likely to be affected, but in manual labourers, then the fingers are more likely to be affected than the toes. They are parallel to the direction of the finger, and will often appear dark. Occasionally they may appear red. Some claim that IE splinter haemorrhages are more likely in the distal part of the nail, although there isn’t much evidence to back this up. They may only occur in one nailbed – this is still just as valid as if they occur all over. Thus make sure you check both hands – quickly and thoroughly.

- Clubbing – This is mainly seen in respiratory disease, but may rarely occur as a result of IE or congenital cyanotic heart disease. For more info on clubbing, see the definitions at the end of the notes on chest exam. They are caused by suppurative disease – this means any disease that can lead to pus filled cavities, e.g. Corhn’s, UC, empyema, bronchiectesis, CF, fibrosis. They only occurs in late IE (infective endocarditis), thus other signs of this disease will be more prominent.

- Pallor, cyanosis, nicotine staining – note that peripheral cyanosis can occur in most people just if the patient is cold. Central cyanosis is a better indicator of disease and is most commonly seen in the lips and under the tongue.

- Capillary return – press on the nail bed and it should go white. In a normal person, it will return to normal colour within 2 seconds. If it takes longer than this, it could just be dehydration, but it is also possibly peripheral vascular disease.

- Asterixis – check for this as a sign of CO2 retention. Remember the flap may take a while to shows itself if the main cause is respiratory. Also remember not to confuse the flap with a tremor (e.g. parkinsonian or caused by β-2 agonists – e.g. salbutamol. )

- Cyanosis – the hands are not a reliable sign of this. Anyone can get peripheral cyanosis on a cold day! Thus the tongue and lips are a more accurate measurement method.

Chest

- When you get to this area, look for scars. They may have a midline scar. This will be a sternotomy scar. This may indicate previous valve replacement or by-pass surgery.

- If the patient has had bypass surgery, then there may also be a scar down the leg to indicate where the artery was taken from.

- A scar running from the left axilla diagonally down the back may indicate previous mitral stenosis. This is a thoracotomy scar. It may also be visible on the front of the chest as a line running from underneath the left breast, diagonally up to the left axilla.

- Chest deformities – e.g. sternal depression, scoliosis, kyphosis – these can displace the apex beat, and cause an ejection systolic murmur thus if these are present, as are chest deformities, the deformities themselves are a likely cause. If the beat is displaced for this reason, then it is probably not clinically significant.

Palpation

Palpate the right radial pulse for rate and rhythm – the pulse character is best assessed at the carotid pulse, although you still can get a sense of it in the radial region.

Rate – normal rate is 60-100.

- Bradycardia – pulse of less than 60bpm. Common in young fit people. Also cuased by β- blockers, heart block and hypothyroidism.

- Tachycardia – pulse of greater than 100bpm. Tachycardia in a resting patient is always abnormal. Can also be caused by anxiety, exercise, pyrexia, hyperthyroidism, β2-agonists (salbutamol), hypovolaemic shock, arrhythmia.

Rhythm – either regular or irregular. The heart speeds up in inspiration and slows down in expiration, don’t confuse this with an irregular pulse! This is because in inspiration, the vagus nerve is inhibited, and thus the heart speeds up.

- This irregularity is barely noticeable in those over 40, but in those under 40 it may be more pronounced, and is known as sinus arrhythmia – but don’t let the term confuse you, as it is actually a very normal!

- If there is an irregularity, check if it is irregularly irregular or regularly irregular. In a regularly irregular pulse, there is often a pattern e.g. each 4th beat is missed. However in an irregularly irregular pulse there is no pattern at all. You basically need an EC to determine the cause of the irregularity, however there are a couple of simple other things that might point you in the right direction:

- Atrial fibrillation can cause an irregularly irregular pulse – and this will not disappear on exercise

- Ventricular ectopic beats on the other hand, will disappear on exercise and the heart rhythm will return to normal during the period of exercise.

- The pulse deficit – this is a term used when atrial fibrillation is present. In atrial fibrillation not only is the beat irregular, but the amount of blood pumped with each beat (and thus the strength of the pulse) can also vary with each beat. This is because in atrial fibrillation, the filling time for the ventricles can vary, and thus the stroke volume can also vary with each beat. Sometimes the stroke volume is so low that no beat at all can be felt. If you suspect something like this you may want to listen to the heart at the same time as palpating the pulse. The heart rate you hear will be different from the pulse you feel. The difference between the auscultated HR at the apex and the palpated pulse at the wrist is termed the ‘pulse deficit’. An example might be a HR of 126bpm, but a pulse rate of 116; in which case the ulse deficit is 10bpm.

Taking the pulse – use your second and third fingers, and your watch! Count over 20 seconds and times the answer by 3 to get the pulse. Whilst counting, don’t forget to feel for the rhythm, and comment on this when you have finished taking the pulse.

If you can’t find a pulse – don’t rush! You should leave your fingers in place on the wrist for up to 10s before poking around somewhere else. Most of the time you can find one if you wait long enough.

You feel a regular pulse; but there is just one irregularity – this is likely to be an atrial or ventricular atopic beat; and thus the pulse is ‘sinus rhythm with occasional ectopic beats’

Palpate the left and right pulse together – these can differ if:

- There is aortic dissection (and the differing pulse may help point to where the dissection is)

- There is proximal artery disease (e.g. atherosclerosis or stricture) of thee axillary artery.

- Stricture of the axillary artery can occur after angiography

- Method – feel both radial pulses at the same time – feel the right with your left hand, and the left with your right hand. Feel for a delay. Don’t forget to take your time and relax. Try and get in a comfortable position. If you are straining and leaning you may feel like all the pulses have a delay!

Radio-femoral delay – this is a subtle sign and is not often seen. Normally the radial and femoral pulses will be felt at the same time as they are roughly the same distance from the heart. If there is a delay between them, then it is known as radial-femoral delay.

- It is caused by co-arctation of the aorta. This is where there is constriction of the aortic arch, distal to the left subclavain artery. This means blood flow to the arms is good, but to the legs is poor.

- As well as being delayed, the femoral pulse is weak.

- Blood pressure is also usually elevated

- There is often a continuous murmur over the scapula

- There is often a systolic murmur at the left sternal edge

- You may be questioned as to why you have not included this, if you don’t do it. It may be possible to justify yourself if you say that it is very rare, and you would do it if there was hypertension, or other signs that pointed to co-arctation of the aorta (e.g. the murmurs mentioned above). It can be a bit awkward to do, as it involves you poking round in the patient’s groin right at the start of the examination (when they are expecting you to be listening to the heart!).

Checking for a collapsing pulse – this is a sign of aortic regurgitation.

- Ask the patient if they have any pain in the shoulder

- If not, then raise the left arm, but do not keep your fingers specifically on the pulse – hold the whole wrist. With both hands, hold the forearm (one on the wrist, one lower down), with your fingers generally on the ulnar side.

- You are feeling for the pulse ‘vibrating back down your arm’ – if the pulse does this, then it is a collapsing pulse, and thus a sign of aortic regurgitation.

Blood pressure! – don’t forget to tell the examiner you would check for this, even though it is unlikely you will need to do it in OSCE.

- The patients should be sat down and relaxed

- The arm should be supported to the level of the heart

Face eyes and tongue

- Malar flush – this is also called mitral facies, and is a sign of mitral stenosis. It describes a blue-ish tinge of the cheeks. It is caused by dilation of the cheek capillaries, which is secondary to pulmonary hypertension. Patients with rosy cheeks do not have mitral stenosis! (generally!)

- Xanthelasma and corneal arcus – both signs of hyperlipidaemia, and thus hint at possible atherosclerotic disease

- Xanthelasma is fatty deposits (papules) around the eyes. They are usually yellow, and nearly always suggest hyperlipidaemia

- Corneal arcus also called arcus senilis, is a grey ring around the iris, again a result of fat deposits. These are common in elderly people, and only when present under the age of 50 is it a sign of hyperlipidaemia.

- Anaemia – you know what to do! Don’t forget to ask the patient’s permission before jabbing your fingers near their eyes. Remember this is a bit of a poor sign!

- Central Cyanosis – Check under the tongue for blue tinge – possible sign of cyanosis – see respiratory exam for more on this. The most common cause of central cyanosis is pulmonary oedema. Pulmonary oedema may come on suddenly as a result of ischemia or MI, or it can be chronic as a result of heart failure / valve defects.

- Check dental hygiene – poor oral hygiene and gum disease is a common route for bacterial endocarditis.

Carotid pulse

Abnormal pulse character can be caused by a valvular lesion

Changes in pulse character are often very subtle, and thus best judged by feeling the carotid pulse, which is closest to the heart.

Abnormal pulse character

- Aortic stenosis – slow rising, then plateau

- Aortic regurgitation – fast rising (waterhammer) and fast falling (collapsing)

- Mixed aortic valve disease – both stenosis and regurg are present – bissfiriens pulse – double impulse pulse

- Other conditions – abnormalities in the character of the pulse are generally a result of aortic valve problems, however, there are sometimes other causes, for example hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy.

Examining the pulse – get the patient to rest their head on the pillow if possible, and tell them to relax. If they are still tense, you can ask them to ‘slide back down into the bed’.

Correct method for feeling for the pulse – ask the patient’s permission, and tell them it may feel slightly uncomfortable. Then, use your thumb and place it on the lateral edge of the thyroid cartilage – in about the place of the Adam’s apple. Then gradually move laterally and posteriorly until you can no longer feel the cartilage. At this point you should be able to feel the carotid pulse. Then decide on a pulse volume and decide how quickly it rises and falls.

JVP

- Anatomy – the internal jugular vein lies quite deep in the neck, between the sternal and clavicular heads of the SCM muscle. It then travels deep under the SCM up towards the ear. The external jugular vein lies lateral to the SCM and is much more superficial and thus is easier to see.

- JVP waves – the JVP has a waveform, just like the pulse pressure has a waveform. This waveform correlates to various parts of the cardiac cycle.

- Arterial pulsations can be palpated, venous cannot

- JVP has a ‘double wave waveform’

Causes of raised JVP

- Right heart failure – this is by far the most common cause. Right heart failure itself is often secondary to left heart failure (either as a result of ischaemic disease, or less commonly, mitral valve defects)

- Fluid overload – possibly a result of excess fluid intake or kidney failure

- Tricuspid regurgitation – the tricuspid valve does not close properly, thus the JVP directly reflects the right venous pressure and not the right atrial pressure. This causes a massive v wave on the JVP waveform

- Complete heart block – in this situation there is atrioventrricular dissociation and thus the atrial and ventricular contractions are not co-ordinated. Atrial contraction can occur when the tricuspid valve is shut and thus a giant a wave is produced. This however occurs irregularly, as sometimes the atrium will contract when the tricuspid valve is open.

- Superior vena caval obstruction – the JVP will be elevated without pulsation. This is because the JV will be distended. The hepatojugular reflex will be negative and the cause is usually mediastinal lymphadenopathy as a result of lung cancer.

- Atrial fibrillation – in this condition there is no atrial systole thus the JVP wave has no a wave.

How to examine the JVP

- Get the patient at 45’

- Ask them to look to their left (about 30’ angle is good)

- You need good lighting. If this is bad you can always switch on the bed lamp

- Look just above the clavicle between the heads of the SCM

- If you can’t see anything, you can look slightly medial to the SCM and a bit higher up. If there is a pulse here this is probably the JVP (in which case it would be raised)

- You could also check if the earlobe is pulsating – this suggest raised JVP. A raised JVP can cause a waggling ear lobe. Arterial pulsations will not cause this!

- You can also palpate the pulse to check if it is arterial or venous. Generally venous pulsations are not palpable (unless venous pressure is massively high!), but arterial ones are.

- Check for hepatojugular reflux (spelled right!). this is also known as the abdominjugular reflux.

- By doing this you are ensuring that any pulsation you see is venous and not arterial

- When you press on the liver you only increase the pressure slightly for a short time, even if you keep the pressure on the liver. If you press on the liver, and the JVP rises / becomes more prominent and stays like this for longer than a few seconds then the most likely diagnosis is heart failure.

- Arterial pulsations are not affected by pressing on the abdomen

- Always ask if they have a tender abdomen before pressing! Then ask permission to press

- Press gently on the RUQ for about 10s, looking for a JVP, or if you have already seen one, looking if it is increased

- In many patients you may not see a JVP and this is completely normal! However, if you do see it just above the clavicle, this is reassuring as you know you haven’t missed a raised JVP.

- If you still haven’t seen one – then you may be able to fill the external jugular vein yourself and check its emptying. If you press you finger gently on the region you would expect to see a JVP, you may occlude the external JV. This will allow the external JV to fill, and you may see a column of blood rise above your finger then, when you release your finger, the column may fall back down. If it does fall this is reassuring as it normal. If it does not fall back down immediately then it is likely the JVP the pressure in the atrium is raised, and although you haven’t seen the JVP, you can assume that it is raised, or the problems that can cause raised JVP may be present.

- Some argue that the external JVP isn’t reliable because it has valves. But recently it has been shown that the internal JVP also has valves and these do not cause a problem. It’s a bit of a contentious issue, but it is generally now accepted that the external JVP is a good substitute if the real JVP cannot be seen.

- Remember you can’t really see the JVP if the neck is not relaxed. A relaxed SCM should not be very prominent. So unless they are very skinny, then if you can see the SCM, they probably aren’t very relaxed! Ask the patient to just relax their neck and jaw.

- Always try to examine the right JVP! The left JVP may still be reasonably accurate but the pressure of the aorta nearby can affect it. Thus in patients who cannot turn their head to the left, viewing the left JVP may be acceptable.

Inspect the precordium

- Apex/mitral area – around the 5th left IC space, midclavicular line

- Tricuspid area – around the 4th left IC space, just lateral to the sternum

- Pulmonary area – at the 2nd left IC space, just lateral to the sternum

- Aortic area – the 2nd right IC space, just lateral to the sternum

- The left sternal edge – the is the area just lateral to the sternum on the left hand side, and this is significant as aortic regurgitation is best heard here.

- Ask the patient to put their hands on their hips to expose the lateral chest walls, and make sure you inspect here for scars.

Look for cardiac pulsation – this basically just means look and see if you can see the apex beat. You may need to move a woman’s breast to do this properly. Ask her permission before you do this! At the same time you should look for any scars (thoracotomy scar is in this region)

Palpation

Palpate for the apex beat. You are checking both the character and the placement of the beat. A displaced beat is not always clinically significant – it can be due to pulmonary and skeletal abnormalities. The normal apex beat is at the 5th IC space, mid-clavicular line. Like when auscultating the mitral valve , the sensation may be exaggerated by asking the patient to lie on their left hand side, thus bringing the heart closer to the chest wall. Several things can alter the apex beat:

- Mitral stenosis – the beat is ‘tapping’ but is not displaced. The normal apex beat is a product of systole. In mitral stenosis, you feel a normal apex beat and the closure of the mitral valve. Thus the apex beat becomes more abrupt, and feels like ‘tapping’. This will usually be present with a loud first heart sound on auscultation.

- Aortic stenosis and hypertension – these will both obstruct cardiac output. This puts extra strain on the heart, and thus hypertrophy results. As a consequence, the apex beat is sustained and heavy. It may also be slightly displaced downwards and outwards

- Mitral and aortic regurgitation –both these result in a large left ventricle, due to the backflow of blood. This will result in a displaced apex beat – down and out – although the character of the beat remains unchanged, because the outflow of the ventricle remains unaltered.

- Left ventricular dilation –as most commonly seen in heart failure – this will produce a displaced apex beat (down and out). The pulsation will be very diffuse, and it may be possible to feel it right from the apex to the parasternal area

- Left ventricular aneurysms –these produce a dyskinetic impulse – whereby the impulse appears to have several different components

Thrills – these are very rare, and a result of a murmur producing a palpable sensation. They feel a bit like a cat purring. A thrill will nearly always indicate a significant lesion. The most common type is aortic stenosis producing a thrill in the aortic area.

- If you don’t hear a murmur on auscultation, then wonder whether you actually heard a thrill.

- Feel with the palm of your hand over the four valve areas.

Heaves aka Parasternal Heave – a heave is

- Emphysema – the lungs are overinflated, and thus insulate the pulsation.

- Pericardial effusion – there is fluid in the pericardial sac, which again insulates the pulsation

- Dextrocardia – this is rare – it is where the heart is found on the right side!

Feeling for parasternal impulse – aka parasternal heave – place the heel of your hand, with your fingers pointing upwards over the sternum. You will normally feel the movement of respiration, but sometimes you may also feel the parasternal heave – in which case, your hand will be lifted off the patient’s chest. You have to press on quite hard! You may also want to ask the patient to stop breathing so that you are less likely to confuse breathing with the heave.

Percussion

Auscultation

Normal heart sounds

- S1 – this is the noise of the mitral and tricuspid valve shutting – signalling the start of systole

- S2 – this is the noise of the pulmonary and aortic valve shutting – signalling the start of diastole

Splitting of heart sounds

- Splitting of S1 is harder to hear than splitting of S2

- Splitting of S2 is a normal finding – it is often more apparent during inspiration. This is because inspiration lowers thoracic pressure (ie. by the diaphragm contracting), and thus increases return to the heart. Thus the right side of the heart takes longer to fill and thus longer to contract, and thus the pulmonary valve closes later.

- The extra sound after S2 is sometimes called P2 – because it is caused by the pulmonary valve!

Altered heart sounds

- Loud S1 – hear in mitral stenosis.The mitral valve is narrowed, which means it shuts rapidly, making a louder sound

- Soft S1 – occurs in mitral regurg – because the valve does not close completely

- Soft S2 – Occurs in aortic stenosis because of reduced valve movement

- Wide fixed splitting of S2 – s2 is obviously split, and the splitting interval is not altered by respiration. Occurs in cases of an atrial septal defect. The two atrial are connected, and thus there is a large left to right shunt. This makes the right side of the heart have to work a lot harder, and thus ventricular filling on the right is delayed, resulting in the wide split.

- Prosthetic heart sounds – these are often audible even without a stethoscope! Metallic produce a loud clicking sound. Artificial tissue valves usually produce normal heart sounds.

- Metallic mitral valve – will produce a loud ‘opening snap’ which occurs after S2

- Metallic aortic valve – will produce a loud S2, and an ejection click after S1. There will also be an ejection systolic murmur.

More on murmurs

Systolic

Aortic stenosis

This is more clinically severe than mitral regurgitation. It can cause hypotension, left ventricular enlargement, congestive heart failure, cold peripheries. Basically the output of the heart is reduced, as not enough blood can flow through the valve.

- The severity of the stenosis is measured by the press gradient across the valve. In a normal patient, the pressure gradient (i.e. the difference in pressure between the left ventricle and the aorta) is very low (perhaps 3mmHg).

- A patient can probably go on without significant symptoms to have a gradient up to 50mmHg. After this number, the patient would be recommended for surgery. Also f they experienced significant symptoms below this value, they may also be considered for surgery.

- The murmur can be heard most prominently over the aortic area. It often radiates to the carotid, and thus can be heard in the neck – don’t forget to ask the patient to stop breathing for a second when you listen here – you don’t want to be deafened!

- if there is a murmur present in the carotids, but not at the aortic area, then the noise may be a carotid bruit.

- The murmur tends to be shorter in duration than a mitral regurg murmur, and has a ‘crescendo-decrescendo’ sound.

- The murmur does not always start straight after S1 – there may be a short gap.

- Aortic sclerosis is common in older people, and is due to thickening, but not stenosis of the aortic valve. It will produce a similar murmur to aortic stenosis, but the murmur will not radiate to the carotids.

Mitral regurgitation

This will produce a similar sounding murmur – they both sound like – lubb (swoosh)dub.

- Mitral regurg is generally a bit quieter

- The murmur can be heard most prominently in the region of the apex, and it often radiates around into the axilla.

- The second heart sound may be absent

- It is often of uniform volume, and lasts the whole of systole…UNLESS caused by mitral prolpase, in which case it will start half-way through systole, and be preceded by the mid-systolic click of the prolapsing valve.

- Hypertropic obstructive cardiomyopathy often causes damage to the papillary muscle and can result in mitral prolapse. The murmur of mitral prolapse is a late-systolic murmur.

- Causes of mitral regurg:

- Rheumatic heart disease

- Infective endocarditis

- Ischaemic heart disease

- Post-MI

- Cardiomyopathy

- Atrial fibrillation

- (Congenital)

Diastolic

Mitral stenosis – this produces a mid-diastolic murmur that often sounds like a click followed by a whoosh. It is often associated with atrial fibrillation. It is rare to hear this anywhere other than the mitral area, and you may have to get the patient to lie on their left hand side to bring the valve closer to the stethoscope.

- Causes – Rheumatic fever

Aortic regurgitation

This is the most common cause of diastolic murmurs. It is an early diastolic murmur. This murmur will often be high pitched, and begin loudly then get quieter. This is best heard with the patient sitting up in bed (sitting forwards) at the left sternal edge, with the patient holding their breath at the end of expiration. This brings the valve closest to the stethoscope.

Extra heart sounds

Third heart sound (S3)

This is a low pitched sound (and thus best heard with the bell). You should listen in the mitral area. It comes right after S2, and thus sounds like a double S2 sound.

- The full physiology is not known. It occurs right at the start of diastole when filling is most rapid. It could be related to a non-compliant ventricle and unusually rapid filling of the heart

- It is a normal finding in young fit people and pregnant women – probably because these people have a large stroke volume.

- It is also often present in left ventricular failure. This is because in LVF the left ventricle is often non-compliant, and the sound is produced even though the stroke volume is low.

- It is also present in mitral and aortic regurg; because the stroke volume is high to compensate for the regurg.

Fourth heart sound (S4)

Again, it is low pitched and again, best heard with the bell in the mitral area. It occurs just before S1, giving the impression of a double S1 beat.

- It is never normal. It results from atrial contraction pushing that last bit of blood into the ventricle, and occurs when there is a very non-compliant ventricle.

- It occurs in conditions such as aortic stenosis, hypertension, CCF, hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy

- If both the third and fourth heart sounds occur together, it is known as a summation gallop.

- Remember that S3 and S4 are difficult to hear! Even cardiologists often disagree as to their presence.

Additional noises

- Opening snap – this occurs in mitral stenosis and is the noise of the mitral valve opening. It is best heard at the mitral or tricuspid areas. It is a high pitched snapping sound (so best hear with the diaphragm) heard after the second heart sound.

- Ejection click – this is the sound of the aortic valve opening and is again not normally heard. It can be audible in aortic stenosis (often congenital). This click is best heard in the aortic area, after the first heart sound. It will be followed by the murmur of aortic stenosis.

- Mid–systolic click – this is caused by the mitral valve prolapsing. Half- way through systole, the pressure in the ventricles will have risen to such a level as to prolapsed the mitral valve (in those with a motral valve defect) This will force it into the atrium, and cause the clicking sound heard. There will then also normally be a degree of mitral regurgitation. Thus the ejection click and mid-systolic click are both heard in systole, and are both followed by murmurs. The difference between the two being that the ejection click occurs at the start of systole, and the mid-systolic click occurs some part through systole, and that the ejection click is best heard in the aortic area, and the mid-systolic click best heard in the mitral area.

- Pericardial friction rub – this is a sign of acute pericarditis. It is a scratching sound that can be heard in either systole or diastole. It can vary from hour to hour – like the pain of pericarditis It is best heard at the left sternal edge with the patient sat up and holding their breath after full expiration It is thought to be caused by the visceral and parietal surfaces of the pericardium rubbing together when the surfaces are inflamed.

- Start at the mitral area with the diaphragm. If you hear a murmur, you may want to listen if it radiates to the axilla (more likely mitral regurg), and also have a quick listen at the aortic area to see if it is louder here (aortic stenosis).

- Get the patient to roll onto their left hand side, and listen at the apex with the bell. This is good for hearing the low-pitched murmur of mitral stenosis (mid-diastolic)

- You could also listen at the tricuspid area for tricuspid stenosis, with the patient lied flat

- Get the patient to lie flat. Listen at the tricuspid region. You are listening for tricuspid regurg, pericardial rub and innocent flow murmurs. You may also be able to here the opening snap of mitral stenosis here (mid-diastolic)

- Listen at the pulmonary area with the diaphragm for pulmonary murmurs. You should not uses the bell at the pulmonary area

- Listen at the aortic area for aortic stenosis/sclerosis, again just using the diaphragm. You should not uses the bell at the aortic area either.

- Listen at the right and left carotids for radiating sounds of aortic stenosis, and for bruit (whooshing at the carotids, but no sign of murmur at the aortic region).

- Finally, get the patient to sit up, and listen at the left sternal edge with the patient holding their breath at the end of full expiration. Here you are listening for aortic regurgitation. Let the patient know they can breathe again before you move on!

- You may also want to listen to the lung bases. If you hear crackles at the lung bases, these could be a sign of left ventricular failure (causing pulmonary oedema).

Final bits

Peripheral oedema

- Press for 5 seconds on the medial aspect of the shin, then remove your finger and see if there is pitting

- If there is not, the press again, this time for about 30s. If there is pitting this time, then it could be that the fluid is of higher protein content than if it had pitted at the first attempt.

- If oedema is present you should note its distribution. Often it may not persist above the level of the knee, but in some patients it may be so extensive that it goes all the way up to the abdomen, and the abdomen is also swollen.

Peripheral pulses

- Posterior tibial – use your index finger, and feel behind the medial malleolus

- Dorsalis pedis – use your first two fingers and feel on the dorsal surface of the foot, just lateral to the tendon to big toe. You might have to press down quite hard against the tarsal bones

- Femoral – this is difficult to feel in fat people. The patient needs to lie flat, and feel half way between the pubic tubercle and anterior-superior-iliac spine. Tell the patient what you are doing – don’t just dive into the groin!

- Popliteal – bend the patient’s knee to 120’. Put your thumbs on either side of the front of the patient’s knee, and feel with your fingers in the popliteal fossa.

Sacral oedema

Pulsatile liver

- First have a superficial palpation of the liver to see if you can feel anything

- Then do the normal method of examining the liver, by pressing on hard and moving up from the iliac fossa. Don’t forget to ask for pain and tenderness before you start!