Contents

Introduction

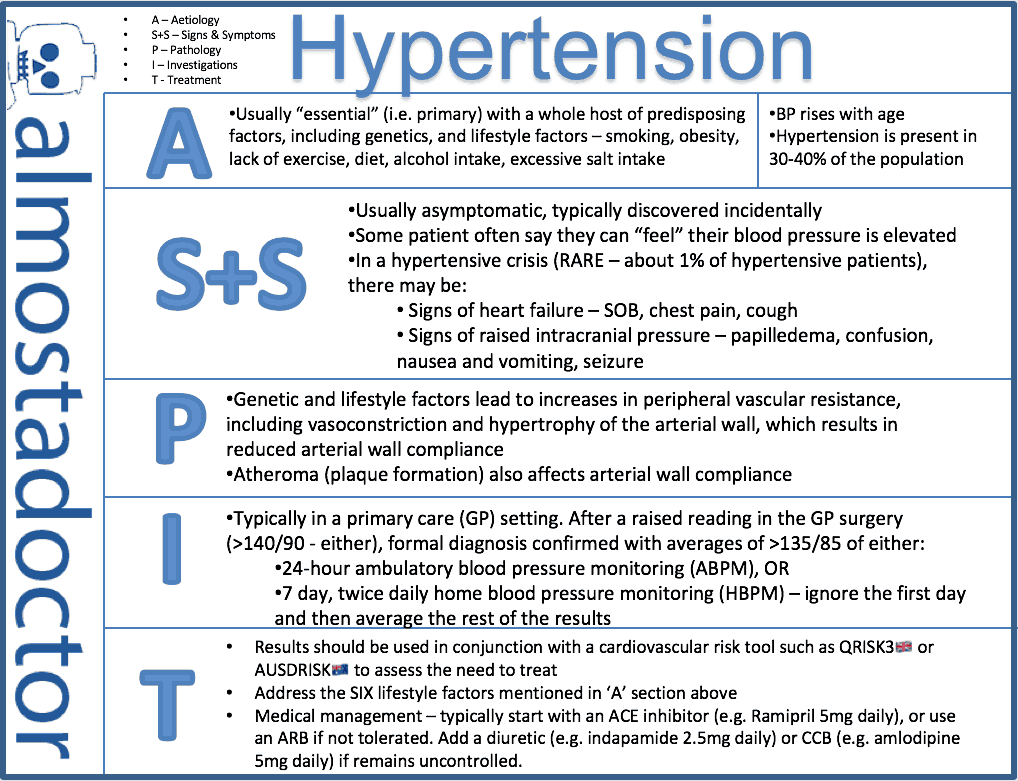

- Mild – >140 systolic or >90 diastolic

- Moderate – >160 systolic or >100 diastolic

- Severe – >180 systolic or >110 diastolic

Diagnosis should involve measurement of BP in both arms during a consultation, and if it is raised, then the diagnosis should be confirmed with either ambulatory home blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) or home blood pressure monitoring (HBPM).

Once the diagnosis is confirmed, the patient should be investigated for target organ damage, and they should be assessed for their risk of cardiovascular disease with a cardiovascular disease risk assessment tool, such as QRISK3 (UK) or cvdcheck (Australia).

They are broadly equally effective. It is thought that the reduction in cardiovascular disease risk is mainly related to the reduction in blood pressure, regardless of the mechanism used. Up to 70% of patients will not have adequately controlled BP with a single agent. It is very common to combine multiple medications to achieve an acceptable BP.

ACE inhibitors or ARBs are recommended as the first line drug, as it is thought they have slightly better long-term cardiovascular disease outcomes.

The first-line recommended combination is ACE-inhibitors (or ARB) with a calcium-channel blocker. This have been proven superior to combinations with thiazide diuretics.

Other drugs that can lower BP – such as alpha-blockers and beta-blockers are not routinely recommended for treatment of hypertension because they have been shown to be inferior at reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease.

Hypertension is rarely an emergency unless associated with signs of end organ damage, and thus is typically managed in the community. A hypertensive emergency (aka malignant hypertension) presents with acute signs and symptoms and needs urgent admission to hospital.

Epidemiology

- BP rises with age (up to the 7th decade). This rise is more pronounced in the systolic pressure, and more common in men

- Hypertension is present in roughly 30-40% of the population

- Hypertension is more common in black Africans – 40-45% of adults

Pathology

It has multifactorial aetiology

Genetic factors – high blood pressure tends to run in families. 40%-60% have a genetic component

Foetal factors – low birth weight is associated with hypertension (and also CVD) in later life. This could be due to adaptive changes the foetus makes in the uterus to under nutrition. These changes could change the structure of arteries, resulting in hypertension later in life. Hormonal systems may also be altered

Environmental factors:

- Obesity – heavier people have a higher blood pressure than lighter people. However – there is also a tendency to overestimate the BP when it is measured with a small cuff on a large arm

- Sleep apnoea is also associated with obesity, and strongly associated with hypertension

- Alcohol intake – there is a very strong correlation between alcohol intake and blood pressure. However – people who consume small amounts of alcohol tend to have a lower BP than those who consume none at all.

- There is a “J-shaped” curve for the graph of alcohol intake and blood pressure.

- Interestingly, similar J-curves are seen for alcohol and all cause mortality, and BMI and all cause mortality. These J-curves have implications for mortality and public health – which is fascinating, albeit well beyond the scope of this article.

- Sodium intake – this is perhaps somewhat over-exaggerated. There is currently no strong evidence that consuming a high sodium diet is causal in hypertension, only that it exacerbates existing hypertension. Nevertheless, those with a high sodium diet have a higher BP than those with a low sodium diet. High sodium diet is also associated with a western, urbanised lifestyle.

- It is thought that a high potassium diet may be protective against a high sodium intake

- Stress – acute stress and pain raise BP, but the association of chronic stress and BP is uncertain (there probably isn’t much association)

- Insulin intolerance – the metabolic syndrome (aka metabolic syndrome X) – this is a syndrome that greatly increases the risk of heart disease and diabetes. The syndrome is said to exist when there is hyperinsulinaemia (i.e. insulin resistance), glucose intolerance, reduced levels of HDL cholesterol, hypertension, and central obesity.

- Renal disease – chronic glomerulonephritis, chronic pyelonephritis, polycystic renal disease, renal artery stenosis. Basically all renal diseases!

- Endocrine disease – Cushing’s syndrome, Conn’s syndrome, adrenal hyperplasia, phaeochromocytoma, acromegaly, corticosteroid therapy

- Congenital disease – coarctation of the aorta

- Neurological disease – raised intracranial pressure, brainstem lesions

- Pregnancy – pre-eclampsia – also causes proteinuria. Eclampsia results in seizures, and other symptoms of malignant hypertension. Patients get many of the features of end organ damage. It is basically malignant hypertension caused by pregnancy

- Drugs – oral contraceptives (oestrogen-containing medications), steroids, NSAID’s, carbenoxolone, sympathomimetic agents, EPO

- Benign hypertension – this is a stable elevation of blood pressure over many years. It is most common in those over 40. The term is not widely used, and the name is a misnomer – because it is not ‘benign’ in the sense that it increases the risk for many diseases

- Malignant hypertension – this is an acute, severe elevation of BP. It is rare, but if undiagnosed, can lead to death within 2 years, as a result of renal failure, heart failure or stroke. It is usually diagnosed due to the presence of retinal signs; Papilloedema, flame-shaped haemorrhages, hard exudates, and cotton wool spots.

Pathophysiology

- There may also be endothelial dysfunction – whereby there is decreased EDRF release (NO).

In arteries (over 1mm in diameter) – muscular hypertrophy of the media, reduplication of the external lamina, intimal thickening. The walls of the arteries often become less compliant.

- There is also a general widespread atheroma.

In arterioles – hyaline arteriosclerosis – this is protein deposition in the arterial wall. The lumen of the artery narrows, and aneurysms may develop.

In the vessels in the brain – microaneurysms (called Charcot-Bouchard aneurysms, and also sometimes miliary aneurysms) can appear

- These aneurysms only occur in very small blood vessels (<300micrometers in diameter), and should not be confused with berry aneurysms.

- They are usually located in the brainstem

- As with any aneurysm, once formed they tend to expand, and possible eventually rupture. When they do rupture, they cause haemorrhagic stroke.

- Hyperplastic arteriosclerosis – this is where there is muscular hypertrophy and reduplication of the basement membrane in arteries. This only occurs in the basement membrane, and thus is different from the changes that occur in benign hypertension. These changes are also often associated with fibrin deposition, in which case the condition is known as necrotising arteriolitis.

- These changes most commonly affect the renal arteries, causing nephrosclerosis which can affect renal function, as well as exacerbating hypertension through the activation of the renin-angiotensin system.

Complications

- Cardiovascular events

- Twice as likely in hypertensive patients as those with normal BP. Examples include:

- Atherosclerosis

- Aortic aneurysm

- Cardiac failure – this is the cause of death in 1/3 of hypertensive patients

- Atrial fibrillation

- Cerebrovascular events – i.e. haemorrhage or clot

- Stroke

- Renal effects

- Renal failure, and other renal problems. Kidneys are more likely to be small than large

- Eye effects

- Visual disturbance – caused by papilloedema and retinal haemorrhages

- Grade 1 – arteriolar thickening, increased tortuosity (twisty-ness), and increased reflectiveness – silver wiring

- Grade 2 – grade 1 + venous narrowing at arterial crossing– arteriovenous nipping

- Grade 3 – grade 2 + evidence of retinal ischaemia – flamed shaped, or blot haemorrhages, and cotton wool exudates (cotton wool spots are associated with areas of infarct. They fade within a few weeks, and thus their continued appearances suggest ongoing pathology)

- Grade 4 – grade 3 + papilloedema (optic disc swelling)

- Adaptive changes – the left ventricular wall hypertrophies (to increase the cardiac output in the face of increased peripheral resistance), and initially, there is no reduction in left ventricular volume. Histologically there is enlargement of myocytes and their nuclei (hypertrophy). However, in the long term, the myocytes will atrophy, and the ventricle will dilate, and have a reduction in muscle volume, causing the complications of left ventricular dilatation and congestive heart failure.

- Hypertension is responsible for ½ of all strokes

- Microaneurysms

Clinical features

- Usually asymptomatic

- May be headaches (not that common)

- Epistaxis (nosebleeds) – but only if the BP is very very very high! Hypertension is not a common cause of nosebleeds

- Signs

- Co-arctation of the aorta could cause radio-femoral delay

- Renal artery bruits

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is not aa straightforward as a one-off reading. Blood pressure varies greatly from minute to minute and day to day. To confirm a diagnosis of hypertension, some form of home monitoring is required.

If hypertension is suspected (e.g. from a one-off clinic reading):

- Repeat BP in the other arm

- If results are variable – use the higher arm for future readings

- Repeat again at the end of the consultation

- If it remains high, then arrange home BP monitoring; either:

- Ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) – the patient is fitted with a BP recording device, which takes their BP every hour (or more) throughout a 24 hour period. Advise the patient to keep doing their normal daily acitivities. Can be inconvenient because it wakes the patient up throughout the night.

- Home blood pressure monitoring (HBPM) – the patient may choose to purchase a BP machine, or loan one for the GP surgery. Ask the patient to keep a diary of their BP:

- Twice daily

- For 7 days

- Take two consecutive readings and record the lowest

- Discard the first day and take an average of the rest of the readings at a follow-up appointment

- Finger and wrist based devices should NOT be used as they are not accurate

- Hypertension is confirmed if:

- Clinic BP of 140/90 mmHg PLUS

- ABPM or HBPM of >135/95 mmHg

- Patient should be relaxed, but not talking

- Read to the nearest 2mmHg

- Repeat in both arms on at least the first occasion

- Repeat after 5 minutes if the first reading is raised

- Remove tight clothing from the arm

- Support the arm at the level of the heart

- Use an appropriate size cuff – the bladder in the cuff must be at least 2/3 the circumference of the arm

- Use phase 5 of the korotkoff sounds to measure diastolic BP

- Phase 4 – this is where the sounds become muffled

- Phase 5 – this is where the sounds completely disappear

- Adults should have their BP measured at least every 5 years up the age of 80

- You should take sitting and standing readings in those with diabetes and the elderly to exclude orthostatic hypotension

Investigations

Every patient with hypertension should be tested for evidence of target organ damage. This should include:

- Bloods:

- HbA1c

- Creatinine and urea (for eGFR)

- Cholesterol

- Urinalysis – dip for haematuria and proteinuria and send to lab for albumin : creatinine ratio (ACR)

- ECG – for left ventricular hypertrophy

- Check fundi for evidence of retinopathy

Other tests to consider if clinical suspicion

- CXR (look for coarctation)

- Aldosterone – for primary aldosteronism

Patients should also have the following baseline observations recorded:

- Height and weight (for BMI)

- Waist circumference

- “Healthy” is defined as <94cm for men and <80cm for women

Management

- In high risk populations – e.g. those with T2DM, then aiming for 120/80 will likely improve their cardiovascular disease risk outcomes

Once the diagnosis of hypertension is established, you should estimate the cardiovascular risk score, with either QRISK (UK) or the cvdcheck tool (Australia). This can help to guide treatment choices. For example, a patient with mild hypertension and a low risk score might opt for lifestyle interventions first, whereas an individual with a high risk score and the same BP might be more inclined to start medication sooner.

Guidelines from various countries are quite similar, but if you want the specifics (as of November 2019):

- NICE guidelines for hypertension (UK) suggest start medication in any patient with stage 2 hypertension as soon as the diagnosis is confirmed, in addition to lifestyle measures. This is defined at BP >160/100 mmHg in clinic (155/95 mmHg with home monitoring readings)

- Australian guidelines suggest:

- High risk (>15% 5-year cardiovascular disease risk) – start antihypertensive immediately

- Medium risk (10-15% 5-year risk) – trial 3-6 months of lifestyle interventions first if patient is well motived, otherwise can start medication immediately

- Low risk (<10% 5-year disease risk) – medication not recommended unless BP is >160/100 mmHg

Lifestyle interventions

- Aim for healthy BMI (18 – 24.9 kg/m2)

- Ask about diet and exercise and advise on a different pattern of these if appropriate

- Advise regular moderate intensity exercise for 30 minutes on at least 5 days per week – a total of 150 minutes per week

- Advise a diet high in fruit and vegetables and fibre, typically similar to the mediterranean diet – e.g. The DASH diet

- Encourage safe alcohol intake

- No more than two units?? (2 standard drinks??) on any one day and 2 alcohol free days per week

- Encourage patients to reduce salt intake, or use a salt substitute

- Offer smoking cessation advice

- Discourage the intake of coffee and other high-caffeine products

- Tell the patient about local initiatives that provide support and promote lifestyle change

- Do not:

- Offer calcium, magnesium or potassium supplements to reduce BP

- Offer relaxation therapies. Patient’s can chose to do them if they wish, but they are not recommended by the NHS

Drug therapies

- ACE inhibitors (or angiotensin-II receptor antagonist if ACE not well tolerated)

- e.g. Ramipril 5mg daily

- Start with low dose if there is evidence of renal failure

- ACE-i and ARB should NOT be used in combination

- e.g. Ramipril 5mg daily

- Calcium channel blockers (CCB)

- e.g. Amlodipine 5mg daily

- Diuretics (thiazide)

- e.g. Hydrochlorothiazide (HCT) 25mg daily, or indapamide 2.5mg daily

- Spironolactone is occasionally used in resistance cases

In cases that are resistant to treatment, other agents that my be considered include:

- Beta-blockers

- Alpha-blockers

- Spironolactone

Generally it is more effective, and has fewer side effects to use multiple agents at a smaller dose, rather than a single agent at a larger dose.

Guidelines

- In most patients – start with an ACE inhibitor or ARB

- If over 55 (or of African origin at any age) and don’t have T2DM then start with a calcium channel blocker

- If a calcium channel blocker is not tolerated, use a thiazide diuretic instead

- In Australia, guidelines are simpler and recommend starting with the ACE inhibitor or ARB first regardless

- If hypertension remains uncontrolled

- ACE or ARB PLUS CCB OR thiazide-like diuretic

- If still remains uncontrolled

- ACE or ARB PLUS CCB PLUS thiazide-like diuretic

- If still uncontrolled – consider this resistant hypertnesion

- Add a 4th agent, such as beta blocker, alpha blocker or spironolactone

Compliance is a big issue in hypertension, because often patients have no symptoms (particularly in essential hypertension) and as such they often feel like they don’t need treatment.

When is it an emergency?

Patients should be considered to have malignant hypertension and referred for emergency hospital management if:

- BP is >180/120 mmHg AND there is papilloedema or retinal haemorrhages OR new onset confusion, chest pain, heart failure or acute kidney injury

Otherwise – it can be managed in the community.

As a doctor who works in the emergency department and general practice, I frequently see patients referred by their GP to emergency for asymptomatic hypertension, when the pressure is very high (typically >180/120 mmHg) without the signs of end organ damage. Usually, there is no need for this.

Info on beta-blockers

These are less effective than the other drugs at reducing cardiovascular risk factors – particularly stroke.

They do not reduce the risk of diabetes – especially in those patients also taking a diuretic, and may, in fact, increase the risk of diabetes.

They are no longer routine therapy, by may be considered in:

- Women of child-bearing age

- Patients with evidence of increased sympathetic drive

- Patients who find it hard to tolerate ACE inhibitors and angiotensin-II receptor antagonists

- If a patient already taking beta-blockers needs a second drug, give them a calcium channel blocker and not a thiazide diuretic. This reduces the risk of developing diabetes

- If the blood pressure is well controlled on a beta-blocker (<140/90), it is not absolutely recommended to change it, however you should consider other options

- Beta-blockers should not be withdrawn, if the patient has another suitable indication for being on one; e.g. symptomatic angina, MI

More management tips

- Treatment is still worthwhile if it lowers the BP, even if it doesn’t reach the target of 140/90mmHg

- If patients are particularly keen to try lifestyle interventions, and their cardiovascular risk is low, then you can try withdrawals of the drug treatment to see if the lifestyle interventions are making a difference.

- Patients should have an annual review – you need to check BP, discuss lifestyle, discuss symptoms and medication.

Wrap-up pearls of wisdom

- Cardiovascular risk increases with BP, even within the ‘normal limit’

- Using the WHO criteria, up to 25% of the population have hypertension

- Hypertension produces structural changes in the heart and cardiovascular system. This causes complications that are referred to as target organ damage.

- Be wary of white coat hypertension – the phenomenon is real! It exists with doctors, and to a lesser extent, nurses. You may weed out many cases of this by taking several readings on different occasions – in cases of white coat hypertension, the readings should gradually approach the normal level. You could also try a 24 hour BP monitor. If white coat hypertension is treated, as ‘real hypertension’, then the patient can suffer serious hypotension when away from the GP’s surgery – and this can be dangerous!

- When you start somebody on antihypertensive medication, it is likely they will be on it for life! Thus you shouldn’t make the decision lightly, and should ensure you have sound readings as a basis.

- Up to 20% of individuals suffer white coat hypertension

- The risk of cardiovascular complications of those with white coat hypertension is much less than those with ‘proper’ hypertension, but still greater than those that exhibit no white coat hypertension.

- 24 hour BP measurements are chronically lower than those in a clinical setting – by approximately 12/7mmHg, and as such, they must be adjusted. Also, note that you take an average of the BP during the day not during the night

- The threshold for diagnosing hypertension from home monitor readings is 135/85

- Combinations of multiple drugs at lower doses is better than a single drug at a higher dose

- More likely to be effective

- Less likely to have side effects

- The recommended combination is ACE-i/ARB + CCB

- The ‘ideal blood pressure’ is 120/80 – however, the actual distribution of blood pressures is like a bell curve, so ‘normal’ for some people is very low (or perhaps even very high!)

- Blood pressure measurements for patients with atrial fibrillation with an electronic devices are frequently inaccurate!

Flashcard

References

- Frisoli TM, Schmieder RE, Grodzicki T, Messerli FH. Beyond salt: Lifestyle modifications and blood pressure. European Heart Journal. 2011;32(24).

- Hypertension in adults – Nice Guidline

- Guideline for the diagnosis and management of hypertension in adults – Heart Foundation (2016)

- Murtagh’s General Practice. 6th Ed. (2015) John Murtagh, Jill Rosenblatt

- Oxford Handbook of General Practice. 3rd Ed. (2010) Simon, C., Everitt, H., van Drop, F.

- Beers, MH., Porter RS., Jones, TV., Kaplan JL., Berkwits, M. The Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy