Contents

- Summary

- More Information

- Ulcerative Colitis

- Crohn’s Disease

Summary

Summary table of Crohn’s disease vs Ulcerative Colitis.

Crohn’s | UC | ||||

Incidence | 5-10 per 100 000 | 10 to 20 per 100 000 | |||

Mean age of onset | 26 Can also present in children – failure to thrive and also in those in their 60’s | 34 | |||

Male: Female | 1.2 : 1 | 1 : 1.2 | |||

Affects | Any part of GI-tract, most commonly the terminal ileum. Also commonly affects the rectum, but not the colon | Only colon, usually more distal regions are worse affected | |||

Mortality | Low | Lower | |||

Surgery required in | 50-80% | 20% | |||

Skip lesions | Yes | No | |||

Mucosal Layers | Deeper | More superficial | |||

Complications | Fistula, abscess, stricture. Most commonly the fistulae come from the anus to the peri-anal region and the produce pus | Rare. Toxic megacolon | |||

pANCA | Negative | Positive | |||

Race | Most common in Caucasians | Most common in Caucasians | |||

Protective factors | High residue, low sugar diet, relatives with Crohn’s means you have an INCREASED RISK | Smoking, appendicectomy, high reside low sugar diet | |||

Pathology | Thought to be very similar in both diseases. In genetically susceptible individuals there is an adverse reaction to bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Normally the reaction against this is self limiting, but in IBD patients once the inflammation starts it may not stop. Thus ultimately it is a kind of autoimmune disease – and the inflammation ends up damaging the gut wall. The diseases follow a relapsing and remising course. | ||||

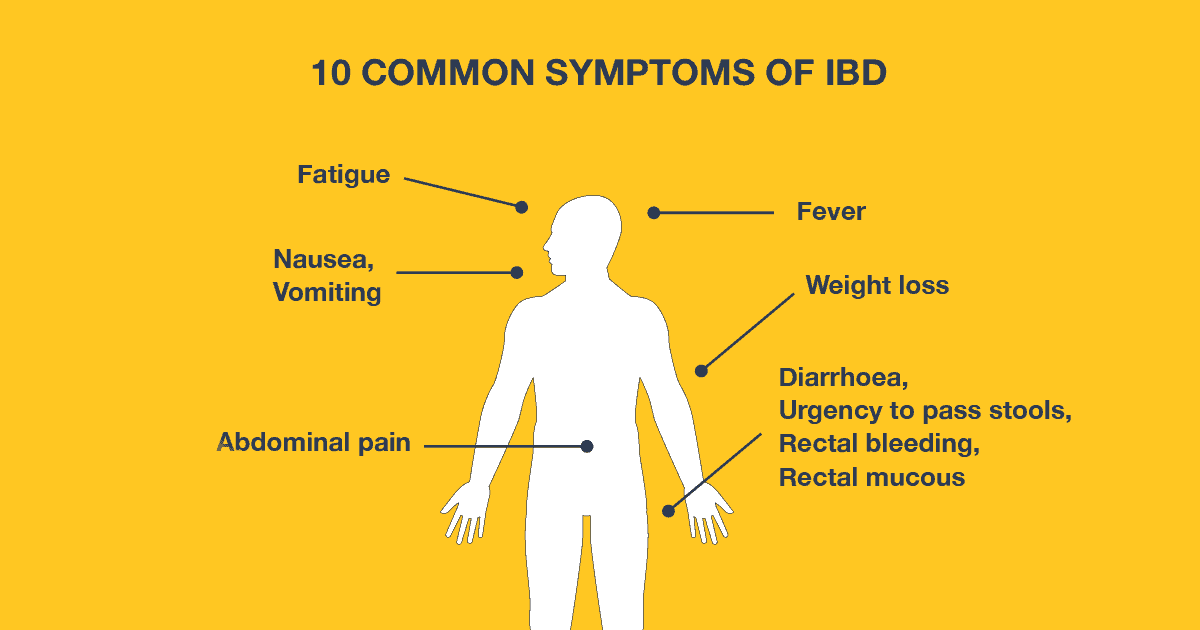

Symptoms | Right iliac fossa mass/pain – this is present even when there is no abscess, abdominal discomfort, blood in the stools, vitamin B12 and iron deficiencies – Crohn’s commonly affects the small intestine and thus can cause malabsorption. | Diarrhoea due to excess mucus production. often also contains blood. Abdominal discomfort, bloating . symptoms usually less severe than Crohn’s | |||

Extra-intestinal symptoms | These are generally the same for both conditions. They include; large joint arthritis, irisitis (like conjunctivitis, but worse), erythema nodosum (red rashes on the shins, more common in UC), ulcers on mucous membranes (mouth and vagina – more common in Crohn’s), cholangitis, pyoderma gangrenosum – this is nasty dead black necrotic tissue. Most commonly found on the legs and around the stoma, renal stones, gallstones, fatty liver, fat wrapping – only occurs in Crohn’s – this is where the messenetric fat spreads around the intestine Crohn’s disease is associated with an increased risk of bowel cancer –this is typically adenocarcinoma of the distal ileum | ||||

Signs | The acute presentation may be mistaken for appendicitis. However, a good history may reveal some facts pointing to a background acute disease. | May be few in mild disease.may include weight loss and malaise. In an acute attack there can be fever, malaise, iron def anaemia, raised WBC, platelets and ESR, hypoalbuminaemia | |||

Barium swallow | This is the most useful test. It can show areas of stricture, shortening of small bowel, fistulas and abscesses | PR | Blood | ||

CT | Will shows areas of wall thickening, strictures and abscesses | CT | Thickened bowel wall | ||

Colonoscopy | Not that useful but can biopsy. Also may help you differentiate pseudopolyps from true polyps | Barium enema | Reduced haustral folds due to fibrosis | ||

CLUBBING! | |||||

Treatment | Cessation of smoking may induce remission in some patients. 5-ASA compounds are not typically used Immunosuppresants used in severe disease. 80% of Crohn’s patients will eventually require surgery. Many require B12 and iron supplements. Low residue diets and low fat diets can help reduce symptoms. Patients may need to be given supplements of the fat soluble vitamins (A D E K). patients are often given antibiotics to reduce the intestinal flora and diarrhoea – metronidazole Infliximab is used in patients that don’t respond to other types of treatment. 70% of Crohn’s patients will respond to it. It is particularly useful in perianal disease | Mild disease: 5-ASA Moderate disease: steroid to initiate remission, then 5-ASA for maintenance Severe disease: trial steroid for 5-7 days. If no remission, then operate immediately. Try to maintain remission with 5-ASA, if not then immunosuppressants may be used. Steroids are often given as a rectal foam | |||

In 10% of cases it is not possible to differentiate from Crohn’s disease or UC, and thus these patients are said to have indeterminate colitis.

Drugs

Drug | Mechanism | Side-effects | Info |

Sulfasalazine* (ASA) | Not fully understood. Thought to trap free radicals released in the inflammatory process | Headache, nausea, vomiting, oligpspermia (low semen volume, but not reduced sperm count), rashes, nephrotoxicity | Can both initiate and maintain remission. Other 5-ASAs include mesalazine and olsalazine. Both are thought to be less effective than sulfasalazine. |

| Corticosteroids | Effective at quickly getting symptoms under control. | Minimal in short-term use. Common in long-term or multiple use patients. | Used in acute flares of moderate to severe disease that has not responded to other treatments. |

Azathioprine | Immunomodulator. Inhibits purine synthesis. reduces the turnover rate of quickly dividing cells | Nausea, vomiting skin rashes, and other similar to other immunosupressants. | Side effects tend to reduce after 6 weeks. Immunomodulators are useful for maintaining remission, but slow to induce remission. Azathioprine is usually the first line immunomodulator. Widely used for maintenance of remission, particularly in CD |

Methotrexate | Immunomodulator. Inhibits the metabolism of folic acid. Reduces the turnover rate of quickly dividing cells | Similar to above | Not licensed for Crohn’s. Evidence for its efficacy is not as good as azathioprine, particularly for UC. |

Infliximab and other monoclonal antibodies | Monoclonal antibody – this is an antibody to TNFα. Prevents TNF alpha binding to its binding site, and thus reduces inflammation. | Not licensed for UC. Other examples of monoclonal antibodies include adalimumab, vedolizumab. | |

| Cyclosporin | Immunosuppressant. Inhibits T cell division. A calcineurin inhibitor – as is Tacrolimus. | Nephrotoxicity, hypertension, hepatic dysfunction, tremor, headache, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, gum hypertrophy, excessive hair growth | Generally a last resort in patients whom are not responding to high dose IV steroids. |

Surgery

Crohn’s | Bowel resection – patients will often have to have several resections during their lifetime. Thus when you operate, you should be as conservative as possible. you should remove the affected area, and 2cm either side. Big wide resections do not decrease the recurrence rate. you should try to avoid small bowel syndrome by resecting too large an area Stricturoplasty In the case of a severe stricture, you can cut the bowel lengthways along the stricture, and then sew it back together to widen the strictured part. Surgery is generally reserved for stricutres, fistulas, disease that does not respond to drug treatments. Abscesses are generally treated by percutaneous drainage and not by surgery Fistulas can exist between parts of the bowel, e.g. between the small and large intestines. These can affect absorption After surgery many patients will have a massive initial improvement in symptoms. |

UC | The whole colon has to be removed, otherwise the disease will return in the part of the colon you have not taken out. You can either have a permanent ileostomy (rare) or a temporary one (restorative protocolectomy). In the restorative surgery, the colon is removed (1% chance of sexual dysfunction in males) and the end of the ileum is then folded over one itself to create a ‘pouch’. This pouch becomes the rectum. It requires two separate operations. One to create the pouch, the other to connect the pouch to the anus. It can be done in one, but this increases the risk of sepsis. After the operation, patients will have to empty the bowel about 5-6 times a day, but there will not usually be urgency. There are often n other symptoms, and thus for many patients, this is better than the symptoms they experiences during exacerbations of UC. Most patients will take anti-diarrhoeal agents at some point. |

More Information

Comparison

- Crohn’s is very rare in the developing world, whilst UC, although still rare is becoming more common.

- Both disease are most common in young adults. There is also a second incidence peak in the 7th decade.

- Crohn’s mean age of onset is 26

- UC mean age of onset is 34.

- Incidence of UC – 10-20 per 100 000

- Incidence of Crohn’s – 5-10 per 100 000

- The main distinction is that ulcerative colitis only involves the colon, whilst Crohn’s disease can involve any part of the GIt from the mouth to the anus. Crohn’s most commonly affects the distal ileum, however, differentiating between the two diseases can be difficult when Crohn’s also involves the large bowel.

- Crohn’s tends to affect the terminal ileum more than anywhere else. ‘Satellite ‘ lesions may occur in the skin, distal from the main affected region, but these are rare. It is also quite rare for any region outside of the small and large intestine to be affected.

- Both diseases are more present in the west than the rest of the world. Non-whites are less likely to suffer, whilst there is a specifically high incidence amongst the Jewish community.

- Crohn’s disease is slightly more common in females than males

- Crohn’s is very slightly more common in females – M:F – 1-12, but the exact opposite ratio is true for UC.

- Test for pANCA is different in each disease – test is positive in UC and negative in Crohn’s.

- Surgery is required in about 20%of UC, but 50-80% of crohns.

- Crohn’s has ‘skip lesions’ whilst UC occurs in one continuous band of inflammation.

- Crohn’s disease affects deeper layers of the mucosa than UC

- Crohn’s can cause complications such as fistulation and structuring that are rarely seen in UC.

- The extra-intestinal symptoms of Crohn’s and UC are the same.

- Mortality of slightly higher for Crohn’s than UC, although both are relatively low.

Aetiology

- High concordance in identical twins(50% chance if you have twin with disease – 10% chance if sibling, 1/1000 in general population)

- 10% of patients have a relative who also suffers from IBD

- Associated with other auto-immune diseases

- UC is more common in non-smokers and ex-smokers

- Crohn’s is more likely in smokers than non-smokers (3-4x).

- Associated with low-residue, high refined sugar diet

- Appendicectomy protects against UC.

- Bacteria! Certain bacteria trigger the disease.

Ulcerative Colitis

Epidemiology

- Most often affects Caucasians in temperate climates.

- It is very rare in Africa and Asia

- It is roughly 2-3x more common than Crohn’s. Although the incidence of Crohn’s is increasing.

- Incidence varies somewhat across developed contires, however some of this difference can be attributed to the fact that some countries class proctitis as a separate disease, whilst some say it is just UC confined to the rectum.

- Similar incidence between males and females.

Pathology

- There is continuous inflammation, that tends to be worse distally and the rectum is almost always involved.

- The inflammation is generally confined to the mucosa and submucosa. It is this inflammation that leads to excess production of mucous and triggers the diarrhoea.

- Initially, bacterial or dietary antigens are taken up by M cells and pass into the lamina proporia through a ‘leaky’ gap between cells or through a lesion.

- The antigens are picked up by antigen presenting cells in the lamina proporia, causing them to secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-12 and IL-18.

- This effect, coupled with the presentation of antigens to the CD4+ T cells, results in activation of TH1 cells. These secrete further cytokines, attracting many more T cells to the region. This build up of T cells will lead to a full blown inflammatory response, including increased vascular adhesion and all that stuff. This can lead to ulceration and stricture formation.

- There may also be accompanying fever, malaise and anorexia.

Proctitis – this refers UC that occurs only in the last 6 inches of the rectum. It also refers to any form of inflammation in the rectum.

Proctocolitis – means inflammation in the colon and rectum – i.e. more generalised than proctitis

Pancolitis – inflammation affecting the whole of the colon.

Clinical Features

- These vary widely depending on the severity of the disease.

- The most common presentation is bloody diarrhoea in an otherwise fit patient. There may also be mucous and pus in the stool, and some slight abdominal discomfort.

- Tenesmus may occur if the rectum is involved.

- Patients with protosigmoiditis may also have tenesmus.

- There may be generally symptoms of malaise and anorexia.

- Abdominal pain often results from stricture – it comes on after eating – as a result the patient eats less – and may lose weight.

- Urgency and tenesmus – these are related to inflammation of the rectum.

- clubbing

There are many other vague symptoms affecting various areas of the body:

- Mucous membranes – Ulcers in mouth and vagina

- Joints – Arthralgia / arthritis in large joints. 10% with IBD get arthritis in the large joints – knees, shoulders, elbows and spine.

- Eyes – Iritis – a deeper inflammation than conjunctivitis. It is inflammation of the iris. 5-10% of IBD sufferers will get this.

- kin

- Erythema nodosum – painful itchy raised round lumps in the skin 1-5cm. 5% of IBD sufferers will have these. Most commonly on the legs.

- Pyoderma gangrenosum – pussy dead tissue – a black necrotis ulcerating mass. Most commonly on the legs or around the stoma. 2% of IBD sufferes will have this.

- Bile ducts / Liver – Cholangitis. This is one of the biggest killers in IBD – death results from liver failure. It occurs in less than 1% of cases of IBD.

Some patients may only ever have one attack, and then be in remission for the rest of their life. 10% of patients will have chronic disease for the rest of their life – i.e. it never goes into remission.

Disease confined to the rectum is generally not pathologically problematic; however it causes ‘inconvenient’ symptoms, such as urgency, tenesmus and blood mixed with the stool. This type of the disease is known as proctitis.

Acute attack

This will cause bloody diarrhoea and the patient may pass liquid stools up to 20x a day. Sometimes they pass only mucous / blood (i.e. no faeces). This trend may also continue during the night ans is very disabling for the patient.

Other signs of an acute attack include:

- Fever (>37.5’)

- Tachycardia (>90bpm)

- ESR >30mm/hour

- Anaemia – <10g/dl haemoglobin

- Albumin – <30g/L

The disease often starts off in the rectum and then progresses up the colon. Very occasionally the distal ileum will be affected, but this is thought to be chronic inflammation as a result of incompetence of the ileocaecal valve, rather than direct pathology affecting this part of the small bowel.

Examination

- There are no obvious signs to look for in UC. The bowel may be slightly distended and tendr to palpation. The anus is usually normal.

- Rectal examination will usually show the presence of blood.

Investigations

PR exam – this may show blood on the glove

Rigid sigmoidoscopy – this will often show abnormal inflamed bleeding mucosa. There may also be ulceration and friability. In very rare cases, the rectum is not involved in the disease and thus the sigmoidoscopy will be normal.

Blood tests – in acute attacks, the following may be observed

- Raised white cell count

- Raised platelets

- Iron deficiency anaemia

- Raised ESR

- Raised CRP

- Hypoalbuminaemia (in more severe disease)

- pANCA may be positive – in Crohn’s disease this is usually negative.

Stool samples – should always be taken to exclude infective causes of colitis.

Plain AXR– may show the presence of air in the colon and colonic dilatation.

Ultrasound – may show thickening of the wall and the presence of free fluid in the abdominal cavity

CT –often used in acute attacks

Most of the imaging techniques above are only used in acute attacks – but this is when the patient presents anyway!

Colonoscopy – is unusual as an investigation in Crohn’s as it should not be performed during an acute attack. In gives a better view of what’s going on than a barium enema. In long-standing chronic disease it is used to assess the extent of the disease. In patients with disease of more than 10 years, colonoscopy should be performed to obtain biopsies of the affected areas to rule out the possibility of malignancy. It is particularly difficult to pick up malignancy on scans due to the appearance of the disease on such tests – i.e. the pathology of normal UC seen on a scan could ‘hide’ the presence of malignancy.

Barium enema – this will show the macroscopic extent of the disease as well as any ulceration. It will show loss of haustral and possibly a shortened colon as a result of scarring and fibrosis.

Rectal biopsy – this may show inflammatory infiltrates, goblet cell depletion, mucous ulcers and crypt abscesses.

Complications

- Perforation

- Bleeding

- Toxic megacolon

- Venous thrombosis – you should consider prophylaxis in hospital once diagnosis is confirmed

- Colon cancer – there is a 15% risk in patients who have had a pancolitis for 20 years or more.

Treatment

Corticosteroids

Mechanism

Metabolic actions

- Carbohydrates – Glucocorticoids cause a decrease in the utilization of circulation glucose, and an increase in gluconeogenesis. This leads to a tendency for hyperglycaemia. There is also an increase in glucose storage, which is probably a result of increased secreted insulin as a response to the hyperglycaemia.

- Proteins – causes increased catabolism and decreased anabolism – i.e. they cause an overall increase in ‘metabolism’ – breakdown of products to release energy, but a decrease in ‘growth’. Overall there is an increase in protein breakdown, and a decrease in protein synthesis – which can lead to muscle ‘wasting’.

- Fats – has an effect on lypolitic hormones, and causes a redistribution of fat, like that seen in Cushing’s syndrome (e.g. Moon face and buffalo hump)

- Electrolytes – glucocorticoids tend to reduce the amount of calcium in the body by reducing its uptake from the GIt, and increasing its excretion by the kidneys. This can induce osteoperosis. Glucocorticoids are also likely to cause sodium retention and potassium loss.

Regulatory actions

Hypothalamus and anterior pituitary – causes a feedback effect resulting in reduced release of endogenous glucocorticoids

Cardiovascular system – reduced vasodilation and decreased fluid exudation (oozing)

Musculoskeletal system – decreased osteoblast, and decreased osteoclast activity

Inflammation and immunity –

- Acute inflammation – decreased influx and activity of leukocytes

- Chronic inflammation – decreased activity of mononuclear cells, decreased angiogenesis (development of new blood vessels)

- Lymphoid tissues – decreased action of B and T cells, and decreased release of inflammatory mediators by T cells.

- Decreased production of cytokines

- Decreased expression of COX-2 and thus decreased prostaglandin synthesis

- Decreased generation of nitric oxide

- Decreased histamine release from basophils

- Decreased production of IgG

- Decreased complement components in the blood

- Increased anti-inflammatory factors such as IL-10 and annexin-1

- Overall, this results in decreased immune response – both to acquired auto-immune problems, but also to the protective role of the immune system.

Unwanted effects

These are most likely to occur with large and/or prolonged doses.

- Poor wound healing

- Peptic ulceration

- Cushing’s syndrome – which is basically a manifestation of all the metabolic and systemic effects described above.

- Diabetes – as a result of the hyperglycaemia

- Weakness and muscle wasting

- Stunted growth in children – particularly if the treatment is continued for more than 6 months – even if the dose is low.

- CNS effects – often the patient may experience euphoris, but it can also manifest as depression. In depressed patients, the depression may be due to a disruption of the circadian rhythm secretion of the steroids.

- Oral thrush (candidasis) often occurs when the drugs are taken orally, as a result of suppression of local inflammatory processes.

Pharmacokinetics

5-ASA compounds

- First line treatment (induction of remission) of mild to moderate UC

- Mainting remission in UC

- They are less effective in Crohn’s disease

- Note that sulfasalazine is metabolised to mesalazine in the gut

- About 20% of sulfasalazine is absorbed by the small intestine.

- The rest remains in the gut lumen and travels to the large intestine, where the bond between the two components (sulphapryridine and mesalazine) is broken by floral bacteria. In some drugs the breaking of this bond is pH dependent – i.e. it breaks at a certain pH, and thus is targeted to a certain part of the GIt. It is not until this bond is broken that the compound has a therapeutic effect. Very little of 5-ASA is absorbed, and it exerts its effect from the lumen itself.

- Sulphapyridine is absorbed, and it metabolised by the liver.

- In some patients, the pH of the colon may be affected by the disease, and as a result, some preparations of 5-ASA in certain patients may pass into the faeces intact.

- The drug can also be given without the sulfapyridine component, and in such cases it is known as mesalazine. However, this is nearly all absorbed in the gut when given orally, and as such it is clinically less effective than sulfasalazine.

Mechanism

Unwanted Effects

- Headache

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Rashes

- Oligospermia – low semen volume – NOT a low sperm count

- Agranulocytosis – reduced granulocytes (WBC’s) in the blood

- Nausea, diarrhoea, abdominal pain

- Headache and flushing

- Nephrotoxicity – chronic interstitial nephritis and renal impairment

- Skin rashes

Immunosuppressants

- Nephrotoxicity. Almost always occurs. The damage caused is usually temporary but can be permanent.

- Hypertension – occurs in about 50% of people as a result of fluid retention

- Hepatic dysfunction

- Tremor

- Headache

- Excessive hair growth and gum hypertrophy

- Anorexia, nausea, vomiting

Monoclonal Antibody – aka TNFα antibody

Unwanted effects

- Dyspnoea and headache

- Fever, chills, pruritis and urticaria after infusion (15% of people)

- Increased risk of serious infection.

- 12% of patients will develop antibodies to double-stranded DNA as a result of the apoptosis induced by this drug.

Surgery

Pre-operative management

Surgical Options

Restorative proctocolectomy – this involves total removal of the colon and rectum, however, the anal canal and sphincter and associated nerves are left in place for anastomosis. It is possible to perform the whole procedure in one go, but this is associated with higher morbidity and mortality (probably due to the steroids the patient will be on to trea the UC), and so is usually carried out in two or three steps. You need to leave in at least 2cm of anus to rejoin the bits together later on. This surgery carries a 1% risk of sexual dysfunction in males.

The best thing about this surgery is that it will only require a temporary stoma. It will usually involve two operations. In the first, the rectum and colon are removed, and a pouch created with the terminal ileum. This will then be left for about 6 months to ‘bed in’. During this period, the patient will have to have a stoma. This temporary form of stoma is known as a loop ileostomy. After this time, the pouch (which now performs the job of a ‘rectum’) will be joined to the anal canal to create a continuous bowel. The stoma can be removed at this stage.

After this procedure, 80& of patients will make a full recovery, and 20% will experience some morbidity. Complications include; sepsis (which may involve breakdown of the anastomosis), small bowel obstructions, and ileostomy problems.

After surgery, most patients will have continued improvement of symptoms for the first 18months. They will defecate 5-6 times a day, and can usually hold off (i.e. there is not urgency).

There may be faecal spotting for 25% of patients during the day, and 40% at night, however full blown incontinence is rare.

50% of patients will use antidiarrheal agents at some stage.

In 2% of patients, the pouch will fail completely, and have to be taken out.

Some patients will experience ‘pouchitis’ where there is diarrhoea, abdominal cramps, tenesmus, fever and a general feeling of unwell. This is usually treated with metronidazole.

Complete protocolectomy and permanent ileostomy – luckily, this is now rarely performed. It is generally used in elderly patients with poor anal sphincter control, those with advanced stage rectal cancer and in those unwilling to undergo the more complex and lengthy treatment that involves anastomosis.

Emergency surgery options

Management of UC

Mild | Moderate | Severe | |

Motions per day | <4 | 4-6 | >6 |

Rectal bleeding | Small | Moderate | Large |

Temp at 6am | Apyrexial | 37.1-37.8 | >37.8 |

Pulse | <70 | 70-90 | >90 |

Haemoglobin | >11g/dL | 10.5-11g/dL | <10.5g/dL |

ESR | <30mm/h | – | >30mm/h |

Inducing Remission

Mild UC

- 5-ASAs are recommended first line and will induce remission in about 30-45% of patients.

- If this is ineffective, then start on oral steroids (e.g. prednisolone 20-40mg/day), or if the disease is distal, give steroid foams.

- If there is improvement, then reduce the steroids gradually (“Tapering regimen”). If there is no improvement, then treat as moderate UC

- 5-ASA compounds are more effective at maintaining remission than inducing remission

Moderate UC

- Give oral prednisolone (starting at 40mg/day), reducing the dose by 10mg/week if there is improvement, and a 5-ASA, and twice daily steroid enemas.

- If the patient improves then gradually decrease the steroids, if not, then treat as severe UC.

Severe UC

- This is where the patient will usually be systemically unwell. They will generally have greater than 6 motions per day.

- Give hydrocortisone 600mg IV every 6 hours.

- Give rectal steroids every 12 hours

- Consider nil-by-mouth

- Give electrolytes and consider blood transfusion in those with severe anaemia.

- Monitor temp, pulse BP and stools.

- Examine them twice daily and check for tenderness, bowel sounds and distension (i.e. you are basically checking it is not perforation, or toxic megacolon is not forming)

- If they improve after 5 days, then treat as moderate UC. If they do not, then consider ciclosporin or infliximab or surgery.

Novel therapies

- Cyclosporin may be given as a very short course to try and induce remission. Long courses are not advised due to risk of nephropathy

- Infliximab is not really advised due to lack of evidence, but may be attempted

- Nicotine for some reason gives better results than a placebo. This also links in with the fact that smoking is a protective factor for UC.

Maintaining Remission

- Once remission has been achieved 5-ASA will maintain remission in up to 70% of patients after one year, although this fall to 50-60% of patients over time

- Sulfasalazine is generally the drug of choice, but in patients where this is not well tolerated, newer 5 ASA’s such as olsalazine may be given. Sulfasalazine should also be avoided in young men where it can induce temporary infertility (reversed when sulfasalazine is ceased)

Administering steroids topically

Course and prognosis of the disease

Crohn’s Disease

Symptoms

- Diarrhoea – generally caused by inflammation in the rectum.

- Abdominal pain

- Weight loss (and failure to thrive in children)

- Fever, malaise and anorexia may be present in active disease.

- Can also cause constipation if the disease is in the terminal ileum, or if the disease causes a blockage.

Signs

- Abdominal tenderness

- Right iliac fossa mass. 70% of Crohn’s affects the terminal ileum – and there may often be an abscess. Even without an abscess there will be pain in this region.

- Perianal abscesses, fistulae, skin tags. The fistulas go from the lower bowel just out to the perianal region, and they secrete lots of stuff.

- Anal / rectal strictures

- The rectum is rarely affected, although the anus often is

- It commonly causes fistulating and / or stricutring disease.

- The mesentery becomes thickened, and mesenteric fat will creep along the sides of the bowel wall towards the anti-mesenteric border. This is called fat wrapping.

- The disease involves all layers of the bowel wall.

- Often the inflammatory and ulcerating nature of the disease can give the bowel a cobblestone appearance, and there may be many pseudopolyps.

- Fistulation and abscesses result from full-thickness penetration of the ulcers.

- The bowel can become thickened due to fibrosis, leading to stricture formation.

- Perianal disease often leads to skin tags, deep fissures, and perianal fistulas and abscesses that come from the anal canal. These fistulas can leak.

- Lymphatic infiltrate is normally seen in all layers of the bowel.

Systemic signs- these are pretty much identical to those seen in UC.

- Clubbing

- Large joint arthirits

- Conjunctivitis

- Fatty liver

- Renal stones

- Pyoderma gangrenosum

Crohn’s disease and cancer

Types of Crohn’s

- Colonic (25%)

- Ileocaecal (40%)

- Small intestine alone (30%)

Symptoms

- Diarrhoea (90%)

- Abdominal pain (55%)

- Anorexia, nausea, vomiting

Investigations

- Barium swallow – this will show strictures, gross mucosal changes and the presence of fistulas. It is also good for showing the length of the bowel. Small bowel enema will give better definition.

- Colonoscopy – allows for a good view of the colon and for biopsies to be taken. These may show histological abnormalities (e,g, inflammation and granulomas) and even when the bowel appears normal. It is also possible to take biopsies of the terminal ileal orifice when imaging of this region is inconclusive. This type of imaging is preferred to barium enema as it allows biopsy, and you can see more.

- CT – can show fistulas, thickening of the bowel wall and abscesses.

- Stool samples should be taken to exclude infective diarrhoea.

Blood tests

- Serum iron and B12 if you suspect anaemia

- CRP (will be raised if disease is active)

- LFT

- U+E

- FBC

- ESR (will be raised if disease is active)

- WCC (will be raised if disease is active)

- Hb (will be decreased in active disease)

- Albumin (will be decreased if disease is active)

Management

Nutritional Management

Elemental diet

Low residue diet

Mild attacks

- In these cases, the patient will be symptomatic but systemically well. Give 30mg/day prednisolone and gradually reduce the dose if the patient improves. Probably doesn’t need hospital admission, but will need to check up on them at clinic every 2 weeks or so.

Severe Attacks

- In these cases the patient may have severe symptoms as well as being systemically unwell with tachycardia and fever. An abdominal mass may be present.

- The treatment is pretty similar to that of a severe attack in UC, except that antibiotics may also be given IV ; usually a cephalosporin and metronidazole. These are to try and correct any bacterial overgrowth that may be present.

- You may also want to consider parenteral nutrition in severe fistulating disease where resection is the next step.

Severe Chronic disease

- This is disease where the patient will have a flare-up whenever the prednisolone dose is dropped below 15mg/day. These patients should be considered for immunosuppressant therapy with azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine. It may take up to 16 weeks on azathioprine before a beneficial effect is seen.

- Pancreatitis and bone marrow suppression as side effects of azathioprine are rare.

- Interestingly, patients who develop the diarrhoea / nausea etc side effects of azathioprine are able to tolerate 6-metcaptopurine.

- Patients who fail to respond to immunosuppressant may be given a weekly intramuscular injection of methotrexate. This will have some sort of effect in 66% of patients.

- Finally, the last line (before surgery) is infliximab. This is given at a dose of 5mg/Kg over a 2 hour infusion, as this method has been shown to be most effective. This will have an effect in 70% of patients.

Surgery

You should remove the most affected part(s) of the bowel and make an end to end anastomosis, you should try to leave 2cm at either side of non-diseased tissue, however in extensive disease this is not necessary (and may not be possible) and so you may end up having inflamed tissue being anastomosed.

Big wide resections do not decrease the recurrence rate.

Surgery should generally be conservative to avoid small bowel syndrome, particularly as many patients will require more than one resection during their lifetime. Therefore surgery is generally restricted to patients with:

- Fistulating disease

- Stricture causing obstruction

- Disease that has not responded to any of the above therapies

- Acute and chronic blood loss (rare)

- Abscess removal (rare – most are now drained percutaneously)

For disease at the distal ileum, there is a 25% chance the patient will need further surgery within 5 years.

Recurrence of the disease is common after surgery, however, for those with a stricture causing obstruction, the patient will notice a massive and immediate improvement in symptoms after surgery.

Nearly all patients will develop an ulcer within 12 months on the ileal side of an ileocolic anastomosis.

As an alternative to resection, a strictureplasty may be performed in patients with structuring disease. This is where the strictured piece of bowel is cut longitudinally along its anti-messenteric side, and then sutured transversely.

The worse the inflammation before surgery, the higher the chance of recurrence.

- Ileosigmoid fistulas – due to ileal disease

- Enterovesical fistuals – causing reccurnet urinary tract infections and pneumaturia

Crohn’s Colitis

- Bloody diarrhoea

- Urgency

- Frequency

Complications of Crohn’s

- Obstruction – due to fibrosis or inflammatory oedema.

- Fistulas – commonly to neighbouring loops of small bowel (which probably won’t cause too much harm) but also to the bladder and vagina. They may also go from the small bowel to the large bowel.

- Perforation

- Abscess formation

- Haemorrhage

- Gallstones – particularly after the terminal ileum has been resected as treatment for the disease. This resection interrupts hepatic circulation, and leads to depletion of bile salts and gallstone formation.

- Renal stones

- Adenocarcinoma of the small bowel – with very poor prognosis.

- Osteoporosis – many patients have reduced bone density at the time of diagnosis. This is thought to be as a result of the combination of chronic inflammation and poor nutrition.

Prognosis for Crohn’s disease

Flashcard

References

- Murtagh’s General Practice. 6th Ed. (2015) John Murtagh, Jill Rosenblatt

- Clinical Update for General Practitioners and Physicians – Inflammatory Bowel Disease – GESA

- Oral 5‐aminosalicylic acid for induction of remission in ulcerative colitis – Cochrane Systematic Review

- Oxford Handbook of General Practice. 3rd Ed. (2010) Simon, C., Everitt, H., van Drop, F.

If I’m not mistaken, “Cessation of smoking may induce remission in some patients” in the table at the beginning should be under ulcerative colitis not Crohn’s.

Thanks